Picking up the signals –

spectral transmissions

from the agora of public dreaming

.

Now playing: Charlemagne Palestine + Tony Conrad – An Aural Symbiotic Mystery

Murdo Eason - From Hill to Sea

walking / writing / between world and word

Like animated clods of black earth suspended in the branches. A murder of crows.

We can feel their collective beady gaze following us as we walk down the single-track road that leads into the hamlet of Pattiesmuir. A fluttering of wings and more descend. It is hard not to think of the gathering flocks in Hitchcock’s The Birds.

For no apparent reason, they suddenly take flight. A spiralling vortex of wing, beak and claw, ascending, then wind-blown towards the white crosses in Douglas Bank Cemetery. Only four return to the upper branches, no longer interested in us. One looks west whilst three gaze towards the east indicating our direction of travel.

Three craws …

The old car at the entrance to Pattiesmuir evokes a sense of time travel as we walk through an agricultural hamlet whose physical fabric has changed very little over the past 150 years. A collection of low-level whitewashed cottages line a single street that provides both entrance and exit with no through road.

we walk through an agricultural hamlet whose physical fabric has changed very little over the past 150 years. A collection of low-level whitewashed cottages line a single street that provides both entrance and exit with no through road.

Pattiesmuir has been recorded on maps as Patiemuir, Peattie Muir, Pettymuir and a number of other variants. An early map from 1654 records it as Pettimuir, although the origin of the name remains obscure. Local folklore suggests that the area was once a focus of Romany activity and even that The King of the Gypsies once had a ‘palace’ nearby. The 1896 Ordnance Survey map does refer to an area of trees to the west of the settlement as “Egyptian Clump”, and a neighbouring field is also noted as “Egypt Field”.

In the early 18th Century a small community of hand-loom weavers formed in Pattiesmuir to help supply the Dunfermline linen industry. By 1841,there was a population of 130 which supported a school – attended by 34 pupils – an Inn, a blacksmith and three public wells. By 1857 the population was 190. However, the introduction of the power-loom meant a slow decline in the fortunes of hand-loom weavers and by 1870 almost all weaving activity had ceased.

There are no schools or Inns in Pattiesmuir these days but a building called The College remains. It’s origins lie in a fraternity of radical weavers who set up the ‘college’ so that weavers and agricultural workers could meet for self-improvement classes in politics, philosophy, economics and theology. They subscribed to the Edinburgh Political and Literary Journal and pooled funds to buy the works of Burns and the new Waverley novels of Walter Scott. One notable member and self-proclaimed ‘professor’ of the College was Andrew Carnegie, grandfather to a Dunfermline born grandson of the same name. Young ‘Andra’ would travel to America in 1848 and eventually consolidate the US steel industry to become the ‘richest man in the world’.

You cannot drive through Pattiesmuir, but if you walk you can take a left where the road stops and walk into a curious area of landscape. Neither edgeland nor particularly rural it is bounded by Dunfermline, only a few miles away, to the north and Rosyth to the East. A rarely walked mix of hedgerows, old woodland, farm tracks and tenanted agricultural land. On Google maps it is an area that is deemed ‘featureless’. However, we already know that it hosts a coffin road and the wild wood. Today’s walk will reveal a few more surprises …

We stand and watch the weather arrive. A huge palm of grey sky that threatens to smother us with rain but growls quickly past. Underfoot, attention is diverted to the heroic efforts of a slug traversing the rough stone path. The intensity of existence revealed in this waltzing fuselage of seal-smooth skin and striated hand-painted detail. Eventually it reaches more hospitable looking terrain and we can walk on.

We are intrigued by the sign on a set of ruined agricultural buildings. Clearly, it has been a long time since they were operational. Part of the roof is missing and internal vegetation is now stretching for the sun.

Minimal Disease Pigs – it could either be the name of an undiscovered hardcore punk band or a fragment from a Mark E. Smith lyric:

Minimal Disease Pigs – it could either be the name of an undiscovered hardcore punk band or a fragment from a Mark E. Smith lyric:

Beware of Guard – uh

Minimal Disease Pigs

No Entry

No Entry – uh

Of course, after the walk we had to find out what minimal disease pigs were:

Many infectious diseases are transferred from the sow to her offspring after birth and breaking this cycle of transference is the basis of the minimal disease concept. If piglets are reared in total isolation from their mother and all other pigs that are not minimal disease pigs (that is they never come in contact with or even breathe the same air as other pigs), they will not become infected with certain disease-causing organisms (pathogens) that are normally present in pigs. Thus the cycle of transfer of many organisms from one generation (the sow) to the next (her offspring) is broken.

There is an almost chilling bio-technocratic language behind this concept. A section on ‘Breaking the Cycle‘ becomes even more so with descriptions of ‘snatch farrowing’, ‘hysterectomy procurement techniques’, ‘euthanased sows’ and ‘total isolation rearing’. It would appear that the minimal disease nomenclature died out, in the UK, in the 1970s to be replaced by ‘High Health Status‘.

It is unclear what happened to the fortunes of this particular pig farm that is now being slowly reclaimed back into the landscape. An agricultural ruin that has given us a partial glimpse into the bio-technic world of the animal husbandry practices that deliver up packets of bacon and pork on to the supermarket shelves. Another connection that illustrates that the urban and rural, local and global can never be viewed in isolation when we consider such basic questions as to how and where do we get our food.

It is unclear what happened to the fortunes of this particular pig farm that is now being slowly reclaimed back into the landscape. An agricultural ruin that has given us a partial glimpse into the bio-technic world of the animal husbandry practices that deliver up packets of bacon and pork on to the supermarket shelves. Another connection that illustrates that the urban and rural, local and global can never be viewed in isolation when we consider such basic questions as to how and where do we get our food.

As we head northwards towards the distant spires of Dunfermline, we encounter another relic of the agricultural past.

Crowned by thorns

an elegy

from the future?

An old petrol pump, presumably used at one time for filling up farm vehicles. Crowned by thorns, nature’s brittle fingers have enveloped the head and spiraled down the structure. Any message that was once conveyed by the sign on the wall is completely effaced. At one level the image perhaps conveys a narrative of decline of the tenant farmer or small farmer in general. As food production becomes increasingly industrialised, the small farmer finds it uneconomic to compete. Like the pig-farm, the infrastructure is slowly being reclaimed by the natural world.

However, is there another narrative? The petrol pump as a potent symbol of the global petrochemical and energy industries that exploit non-renewable resources that will one day inevitably run out. What will the cost be to planet Earth and its lifeforms? Is a crown of thorns awaiting the petrochemical plants, power stations, cars, aeroplanes …?

All questions to ponder as we head over the fields, nodding to the strange, silent wind poetry of Spinner. Just another story layered upon this ‘featureless’ curious landscape.

≈≈≈

Now playing: Hacker Farm – UHF

References:

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Queensland Government, Minimal Disease Pigs

Fife Council Enterprise Planning and Protective Services Pattiesmuir Conservation Area Appraisal and Conservation Area Management Plan, October 2011.

Raymond Lamont-Brown, Carnegie: The Richest Man in the World (Stroud: The History Press, 2006).

.

Beyond the hawthorn, lies the wild wood

“cuckoo, cuckoo”

.

.

over the threshold

forms and colours

of the Otherworld

.

.

… snake-eye stirs

.

‘

jaw click, snout

and a slither

of tongues

.

.

threat or supplication?

paw or claw?

who hears the cry

of the wild wood?

.

.

no-one here

.

anyone?

.

.

the oracle

of the wood

whispers:

.

.

… always the leaves

.

.

… always the light

.

≈≈≈

.

Hawthorn bushes and the call of a cuckoo conjure up the tale of Thomas the Rhymer a thirteenth century Scottish mystic, wandering minstrel and poet. Folklore tells of how Rhymer meets the Faery Queen by a hawthorn bush from which a cuckoo is calling. The Queen takes Rhymer on a journey of forty days and forty nights to enter the faery underworld. Some versions of the tale say Rhymer was in the underworld for a brief sojourn. Others say for seventy years, after becoming the Queen’s consort. Eventually, Rhymer returns to the mortal world where he finds he has been absent for seven years. The theme of travellers being waylaid by faery folk and taken to places where time passes faster or slower are common in Celtic mythology. The hawthorn is one of the most likely trees to be inhabited or protected by the faery folk.

The wild wood can be found amongst the terra incognita of farmland, old paths and hedgerows between the village of Pattiesmuir and Dunfermline, Fife.

Now playing: Bert Jansch – ‘The Tree Song’ from Birthday Blues.

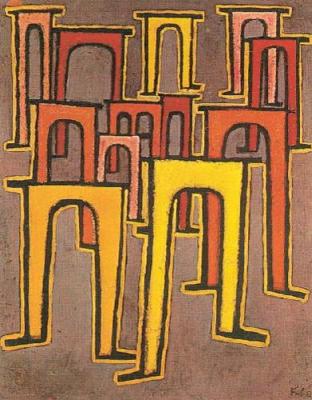

taking a line for a walk ~ Paul Klee

taking a walk on a line ~ FPC

~

Walking Score No I (After Klee)

~

Take a map drawn to any scale

~

Draw a line that starts and ends at the same place

~

Attempt to walk the line as far as is practicable

~

Record your experience in some form and share if desired

~

Now Playing: Wire – Map Ref. 41°N 93°W